Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

- Robert Wiene

- Germany

- Horror

- Silent Film

- Conrad Veidt

- Werner Krauß

- Lil Dagover

- Erich Pommer

- Decla-Film-Gesellschaft, Berlin

- Willy Hameister

- Carl Mayer

- Hans Janowitz

Viewed by producer Erich Pommer as a reasonably inexpensive gamble, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was taken by many of the creative figures involved as an opportunity to adapt the modernist forms developed in the 1910s cinematically and produce the first major international art film. Screenwriters Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz were avowed pacifists and there has long been an argument, best articulated by Siegrfried Kracauer in his pioneering study of German cinema From Caligari to Hitler [1], over the degree to which the critique of authority they intended may have been compromised by the ending.

It was, however, the psychological ambiguity of the film that ensured its enduring impact. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari reflects the unresolved mental shocks of the First World War better than any other film, and its influence can be felt on everything from film noir to Dr. Strangelove (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) to Shutter Island (Martin Scorsese, 2010).

A Completely Designed Film

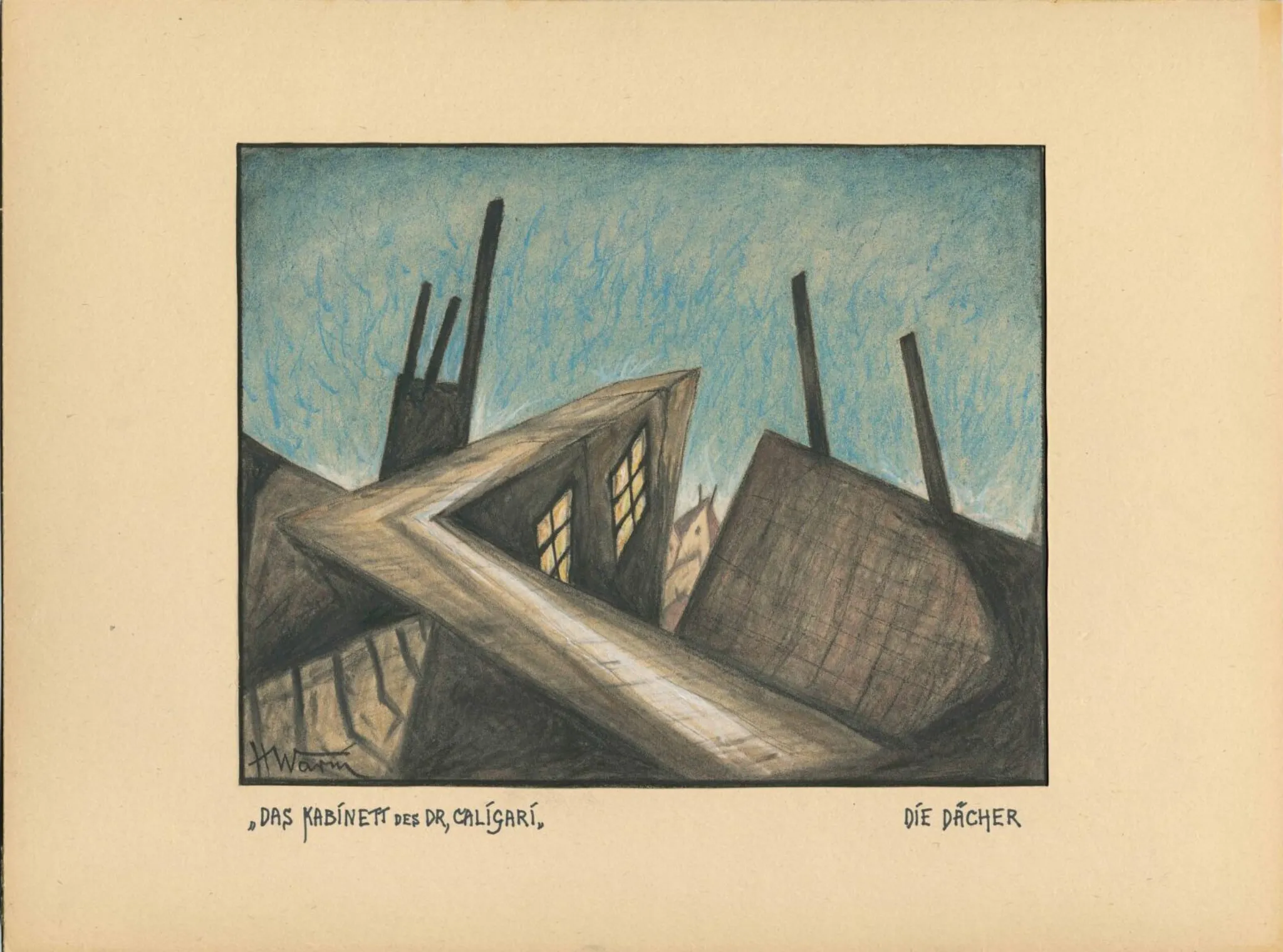

Hermann Warm's set design for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Hermann Warm Archiv, Deutsche Kinemathek)

Expressionist Performance

As Lotte Eisner, an influential German critic and scholar (and later co-founder of the Cinémathèque Française), pointed out decades ago [2], the greatest influence on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was the avant-garde theater of Max Reinhardt (1873-1943). Born near Vienna, Reinhardt became associated with the Deutsches Theater in Berlin at the very moment of cinema's emergence in 1894-1895. Reinhardt gave a prominent role to highly angular sets and associated props, in an attempt to create psychologically resonant tableaux. Production designer Hermann Warm, working closely with Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig, brought his extensive experience with these new theatrical approaches to Caligari. The prominence of these set designs in the resulting film suggests the synthesis of director Robert Wiene's shared interest in Expressionist theater and the architectural background of the original (uncredited) director Fritz Lang.

What separates Caligari from some more set-bound Expressionist films is the complete integration of sets and objects with stark visual contrasts between light and darkness, an innovative lighting and masking strategy in which the edges of the frame remain dimly illuminated and characters seem to merge into their environments, and especially the intense Expressionist performance style of Conrad Veidt. Expressionist acting like Veidt's transformed the pictorial methods of nineteenth century theater through highly amplified gestures that are carefully calibrated with the overall cinematic design to suggest the projection of imbalanced psychic states and the exteriorization of suppressed or unconscious emotions. Theme, style, and plot meld perfectly in the clip below, especially in the shift from ritualized somnambulistic movements suggestive of a hypnotic trance to convulsive gestures that would seem exaggerated and out-of-place in a film with more naturalistic sets and lighting. Appropriately, the sequence ends with a perfect merger of the physical gestures of the hypnotized sleepwalker and the stylized mirror of the natural world that surrounds him.

Orson Welles and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

By the middle of the 1920s, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari had already entered the semi-permanent repertory of organizations like the London Film Society, and it remained widely seen and discussed from the United States to Denmark to Japan. It is therefore unsurprising that theatrical wunderkind Orson Welles turned to Caligari when he was given the unprecedented opportunity to make a feature film on a topic of his choosing with the right to final cut. Welles often said that he learned how to make Citizen Kane (1941) by watching Stagecoach (John Ford, 1939) dozens of times in the private screening room of New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), but he also saw Caligari and its influence is acutely evident in the extraordinary "Crazy House" sequence of The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

The original layout of MoMA had a highly pedagogical structure that would guide viewers from one modern art movement to another. The "Crazy House" sequence playfully twists that through a funhouse mirror while passing from Expressionism to abstraction to surrealism and finally to an echo chamber in which cinema is reduced to its constitutive parts as a series of sequentially placed still images. The emphasis on shattered glass and refracted vision at the end of the sequence provides a new context for the emphasis on glasses and optical devices in Caligari (which, in turn, has its roots in German Romantic fictions like E. T. A. Hoffmann's "The Sandman," 1817 [3]).

Restoration Credits

Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari)

Germany 1920

Production Decla-Film-Gesellschaft, Berlin

Director Robert Wiene

Screenplay Carl Mayer

Hans Janowitz

Production design Hermann Warm

Walter Reimann

Walter Röhrig

Photography Willy Hameister

Cast

Werner Krauß Dr. Caligari

Conrad Veidt Cesare

Friedrich Fehé Francis

Lil Dagove Jane

Hans Heinrich von Twardowski Alan

Rudolf Lettinger Medizinalrat Dr. Olsen / Medical officer of health Dr. Olsen

Restoration (2013)

Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung

Funding

Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA

VGF Verwertungsgesellschaft für Nutzungsrechte an Filmwerken mbH

Der Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien

Material

Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv

Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen

Filmmuseum Düsseldorf

Archivo Nacional de la Imagen – SODRE

British Film Institute

Cinémathèque française

Museum of Modern Art

Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique

Fondazione Cineteca di Milano

Scan, digital image restoration & mastering

L`Immagine Ritrovata, Bologna

Music (2014)

Pablo Beltrán

Martin Bergande

Carlos Cárdenas

Stephan Dick

Vasiliki Kourti-Papamoustou

Hong Ting Lai

Seongmin Lee

Cornelius Schwehr

Carlo Philipp Thomsen

Art director

Cornelius Schwehr

Recording

Clarinet Daniela Kohler, Anri Nishiyama, Hannah Seebauer

Trumpet Gloria Aurbacher, Lukas Fischer, Fabian Müller

Trombone Fabian Grabert, Jonathan Roskilly, Johann Schilf, Karoline Stängle

Drums Li-Ting Chiu, Teresa Grebtschenko, Jerôme Lepetit

Barrel Organ Achim Schneider

Piano Hazel Beh, Damian Glätzer, Sylvia Loh

Violin Nitzan Bartana, Hsu-Mo Chien, Sunhee Moon, Shio Ohshita

Violoncello Andreas Köhler, Gaby Schumacher, Marlena Schillinger

Contrabass Juliane Bruckmann, Lutz Gertler, Martina Higuera López

Conductor and musical direction

Sven Thomas Kiebler

Archive provision

Deutsches Filminstitut – DIF

Museum of Modern Art

Production

Studio für Filmmusik der Hochschule für Musik Freiburg i. Br.

Recording management and postproduction

Alexander Grebtschenko

With special thanks to

Achim Schneider, organ building

Coproduction

2eleven || zeitgenössische musik projekte

Institut für Neue Musik der Hochschule für Musik Freiburg i. Br.

A coproduction of Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung and ZDF in collaboration with ARTE

© 2014