Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

2001's Stargate Sequence and György Ligeti's Hungarian Requiem (1963-1965)

Kubrick and Classical Music

Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) commissioned a full orchestral score for 2001 from Alex North (who he had worked with on Spartacus, 1960), but he rejected it in favor of the music he had been playing on set during shooting, which he then carefully worked into the montage of his films. The result was one of the most influential and celebrated uses of pre-existing classical music in cinema. particularly distinctive for the use of then-very contemporary music by composers like the Armenian Soviet composer Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978) and the Hungarian modernist György Ligeti (1923-2006).

Kubrick and Dance

Early in the film, Kubrick uses Johann Strauss's The Blue Danube (1866), among the most famous of all waltzes and the one most strongly associated with nineteenth century Vienna. In so doing, Kubrick linked his film to the line of filmmakers associated with Vienna (Fritz Lang, Erich von Stroheim, Josef von Sternberg, Otto Preminger, and especially Max Ophüls), inviting comparisons between the ideas of dance, social structure, and performance across centuries.

Kubrick repeatedly switches between linear and curved forms in this sequence and this comparison is given a different inflection later in the film, where the movement of the ship is connected to a running astronaut and the Cyclopean eye of a computer. By shooting inside a specially designed curved platform and rhythmically switching between different vantage points, Kubrick is able to simultaneously convey the nobility of human action and, more ironically, the idea of a hamster on a wheel.

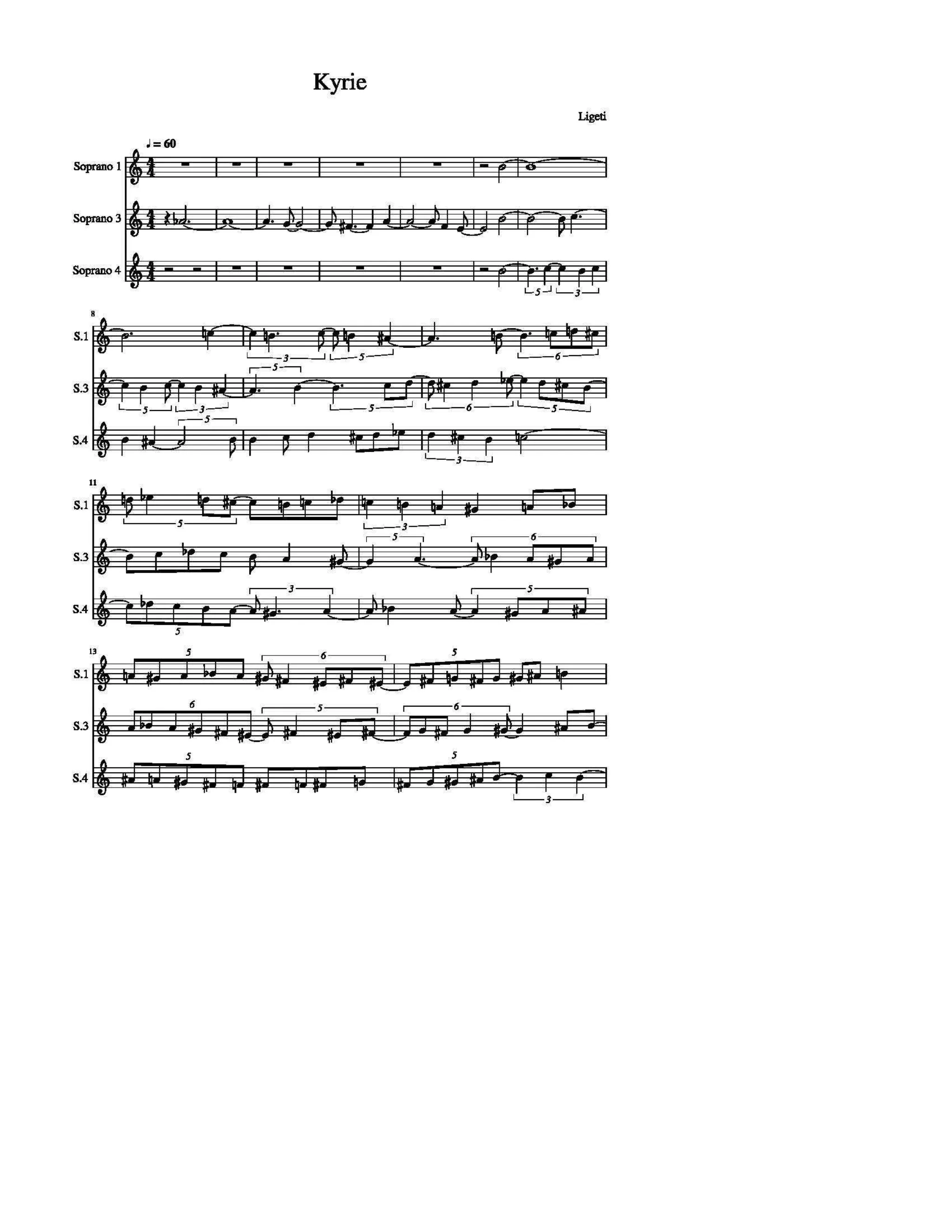

“In my Requiem, which I composed from 1963 to 1965, I set only three segments from the traditional Latin Mass of the Dead: the Introit, the Kyrie and the sequence by Tommaso da Celano. The sequence is divided into two parts: the Dies irae and the Lacrimosa. The Dies irae, with its wild and dramatic passages, lies at the centre of the work. These passages allude to pictorial representations of the Last Judgement, particularly to Memling’s altar-piece in Gdańsk, but also to the apocalyptic paintings of Pieter Brueghel the Elder and Hieronymus Bosch, as well as Dürer’s copperplate engravings. The character of this movement is hysterical, hyperdramatic and unrestrained.

The work is scored for a medium-size orchestra, two solo voices (soprano and mezzo-soprano) and choir. However, as the orchestration is very compact, the choir must consist of at least a hundred singers.

Formally, the piece was conceived as a balanced juxtaposition of homophonic and polyphonic structures: the Introit is homophonic, the Kyrie polyphonic, the Dies irae polyphonic with homophonic 'islands,' and the Lacrimosa, finally, a two-voice homophonic structure with a reduced orchestra.

The Kyrie is a 'great fugue' with five main voices (S, M, A, T, B). Each main voice consists of a four-part canon, resulting in a twenty-voice choral texture. The four-part groups always begin in unison and then fan out into canons following rigorous rules that I established. These rules ensure the unity of the construction. The musical language is strictly chromatic and shows a rhythmic complexity based on imitation, which causes the orchestra to shimmer in iridescent colours. The unison entries of the canonic groups are always supported by instruments, which not only adds colour, but also helps with the intonation; the instrumental parts provide a support structure for the vocal parts.”