Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

Godard's Montage Images

Montage, My Fine Care

Underpinning Godard’s late work generally, and the epic video project Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998) in particular, is an idiosyncratic and expanded notion of montage. For Godard, “montage” refers not simply to the connections between, or even within, shots, but to a mode of vision and experience that lies dormant in raw footage and needs to be discovered through the process of selection and sequencing that is the foundation of the filmmaker’s art. In a 1989 lecture to the film school La Fémis, Godard explained this in terms that evoke the language of André Malraux, “In montage, one encounters destiny." [1]

Godard had used similar language in the most well-known of his early essays, “Montage, My Fine Care” (1956), where he writes that editing “can restore to actuality that ephemeral grace neglected by both snob and film-lover, or can transform chance into destiny.” [2]

In both cases, montage is described using organic metaphors (“a heart-beat,” “something soft, having time to breathe”) and is specifically connected to existential notions of choice, the decisive acts through which the freedom of shooting is converted into the fixed structure of a projectable film, but the contrasts are equally revealing.

In 1956, montage is presented as an aspect of temporal construction that is inseparable from mise-en-scène: “Knowing just how long one can make a scene last is already montage, just as thinking about transitions is part of the problem of shooting.” Godard also isolates one particular use of the brief shot that he sees as fundamental to cinema, the use of glances:

Cutting on a look is almost the definition of montage, its supreme ambition as well as its submission to mise-en-scène. It is, in effect, to bring out the soul under the spirit, the passion behind the intrigue, to make the heart prevail over the intelligence by destroying the notion of space in favor of that of time.

The example Godard provides is the sequence at the Royal Albert Music Hall in Alfred Hitchcock’s remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). In his review of Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956) several months later, Godard once again underscores the interdependence of mise-en-scène and montage, but he places special emphasis on the use of long close-ups in which Henry Fonda stares “abstractedly, pondering, thinking, being.”

What Godard finds extraordinary in them is their ability to “convey the basic data of consciousness,” something they can do precisely because they happen within the normal shot/countershot syntax of classical narrative cinema, a system in which montage is a constitutive but unprivileged element.

Pensive close-ups play an equally important role in Godard's first feature Breathless (1960). He would soon prove to be one of the cinema’s great portraitists, especially of women. In film after film, Godard includes strikingly framed shots of faces held long past the point at which they serve any explicit narrative or dramatic function. These lingering images may have the quality of loving affection (as in many of the portrait shots of Anna Karina in the films of the early 1960s), ethnographic probing, or both, but they almost always depict people in the act of thinking (below).

The shots act as meditative pauses, contributing to the shifting rhythms of Godard’s features, and the montage generally supplies a clear logic for their inclusion by grounding the characters in a particular space. In Histoire(s) du cinéma, Godard uses similar images, culled from throughout the history of the arts, to demonstrate cinema’s status as the heir to a pictorial tradition that he (once again following Malraux) sees as centered on the enigmatic figures of Édouard Manet (below).

Excised from their original contexts and divorced from their narrative motivation, however, the close-ups of women looking in the Histoire(s) du cinéma function as an endless series of incomplete shot/countershots, malleable parts of a continuing dialogue that testifies to the cinema’s power to embalm beauty and to be “a form that thinks,” soliciting questions without ready answers.

Indeed, by the 1980s, Godard’s conception of montage had become altogether more ambitious and mysterious, a way of using inter-shot relationships to create “something like [utopia].” This notion of montage exceeds even that of Sergei Eisenstein, who developed an increasingly inclusive notion of montage that eventually encompassed the core of both European and East Asian modes of representation and that he saw as the highest stage of artistic development. For Godard, by contrast, montage is completely and even definitionally the property of the cinema: “The cinema is the invention of montage. And montage did not exist in the other arts.”

Although Godard shares Eisenstein’s investment in dialectical thinking, he breaks with his predecessor’s conception of artistic progress, positing instead – in both Histoire(s) du cinéma and many of his interview comments – the idea of art engaged in a series of complex negotiations with a multilinear history. More than a synthesis, montage provides access to a new artistic space, a unique moment in which past, present, and future are able to cross-penetrate.

Embedded within this notion of montage is the possibility of organic creation, even of a sort of life-giving magic: “… in montage, the object is living, while in shooting it is dead. It is necessary to resuscitate it. It is sorcery.”

The Image

As Godard’s sense of montage becomes more vast, it also becomes more restrictive. In Seul le cinéma (2A), he tells Serge Daney that neither Eisenstein nor Orson Welles had achieved a true montage, their discovery was the power of angles. He elaborated on this further in the lecture he gave in 1996 upon receipt of the Theodor Adorno Prize:

Eisenstein himself found the angle, preceded by El Greco and [Edgar] Degas. When one looks at his famous images of three lions in October [1928; the lions are in Eisenstein’s earlier Battleship Potemkin, 1925], if the three lions make an effect of montage, it is because there were three shot angles, not because there was a montage.

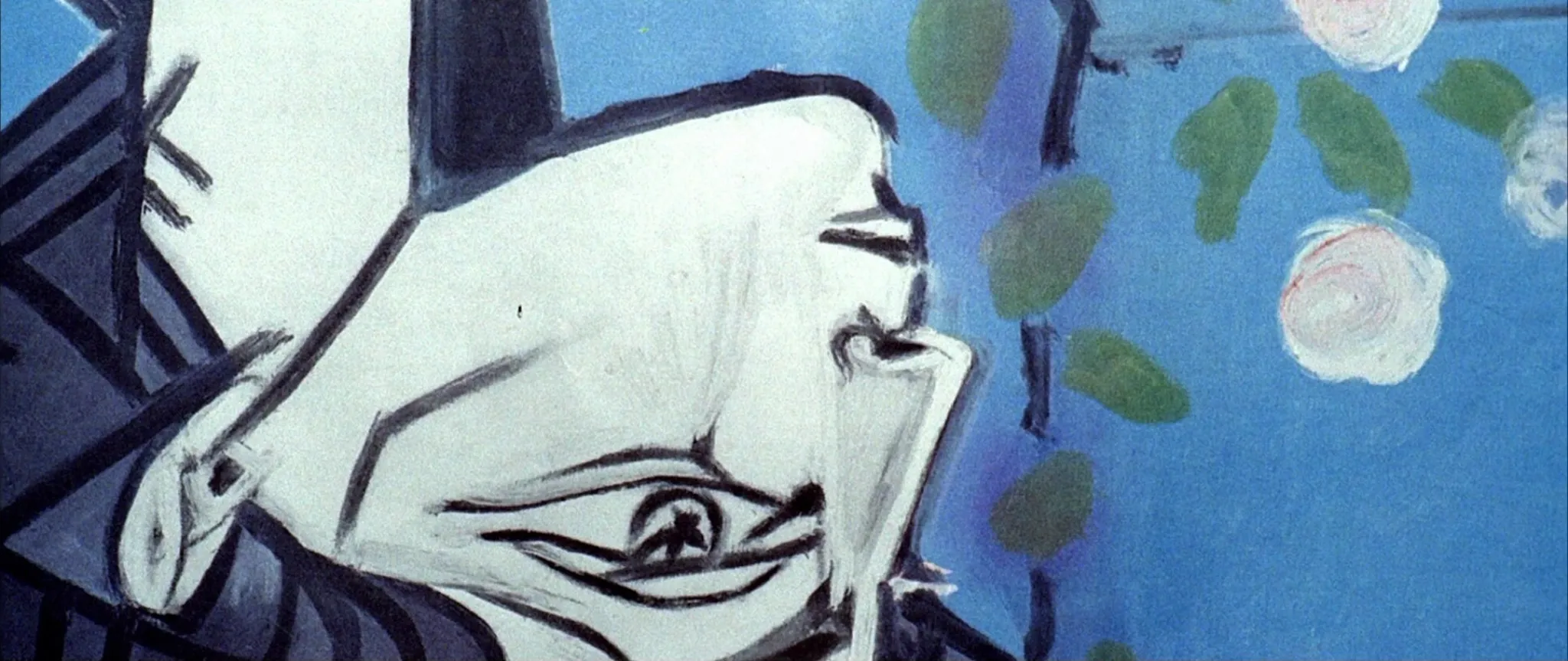

In Godard’s formulation, Eisenstein had mastered the mechanism of montage, but not its ultimate goal: the use of separate images to generate a synthetic Image, the one thing that montage alone can do. By the middle of the 1980s, this had become a mainstay of Godard’s commentaries both within and outside of the films and, as with his ideas of projection, it was expressed most directly in King Lear (above):

The Image is a pure creation of the soul. It cannot be born of a comparison, but of a reconciliation of two realities that are more or less far apart. The more the connections between these two realities are distanced and true, the stronger they get to be, the more it will have emotive power. Two realities that have no connection cannot be drawn together usefully. There is no creation of an image. Two contrary realities will not come together. They oppose each other. One rarely obtains forces and power from these oppositions… An image is not strong because it is brilliant or fantastic, but because the association of ideas is decent and true. The result that is obtained immediately controls the truth of the association. Analogy is a medium of creation, it is a semblance of connections. The power or virtue of the creative image depends on the nature of these connections. What is great is not the image, but the emotion that it provokes. If the latter is great, one esteems the image at its measure. The emotion thus provoked is true because it is born outside of all imitation, all evocation, and all resemblance.

Versions of these ideas are included in Passion, Keep Your Right Up (1987), JLG/JLG – Self-Portrait in December, Notre musique, and Les Signes parmi nous (4B). The underlying principles are central to the aesthetics of his post-1980 work, suggesting a way to use implicit affinities or concordances to create new relationships out of diverse and even contradictory materials.

The central source for Godard’s comments about the Image – unsurprisingly, never cited in any of the films or videos where it has appeared – is Pierre Reverdy. A poet with a penchant for mysticism, Reverdy was a friend of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque who was championed by André Breton in the first Manifesto of Surrealism. [3]

Reverdy started and ran the journal Nord-Sud, which published a number of important Dadaist and Surrealist texts during its brief existence (from 1917 to 1918), including “L’Image,” the poem that Godard borrows from in his discussions of montage. That Godard’s often repeated theory of the authentic Image has its roots in Surrealism reinforces its crucial place in his artistic genealogy. Godard shares with the Surrealists not only an interest in psychic disorientation and a puckish desire to upend the staid proprieties of middle class culture, but also a commitment to transforming photographic realism from within, using it to facilitate the intuitive perception of a lyrical realm more unitary than the one we ordinarily inhabit.

In this sense, Godard’s “Image” could be seen as a contemporary equivalent of the Surrealist “marvelous,” which, in the words of Louis Aragon, is an “eruption of contradiction” that reveals the artificial character of rationalized reality.

Reconciling these twin montage impulses – for Surrealist rupture and historical dialectics – within Histoire(s) du cinéma, and the related films and videos initiated in its wake, necessitated a radical reformulation of the space of the projected image. Godard’s pre-1968 films provoked active engagement through the use of shock cuts, sudden alterations of arrangement or even structure that work only if the spatiotemporal coordinates of illusionistic representation are otherwise respected. A collage-like impression of overlapping layers was created by interspersing different materials, but they were invariably linked to the main body of the narrative through hard cuts. The detritus of the outside world could thus be brought into the larger audiovisual frame of the film, but, despite all the intellectual pirouettes they evoked and the narrative friction they created, the basic documentary recording tendencies of the camera remained unchallenged by these juxtapositions.

During his Groupe Dziga Vertov phase (1968-1972), Godard used a number of different techniques to represent the misperceptions of the viewer (splashing paint on the camera in Wind from the East, 1969, for example), but even the most strident and astringently confrontational of those films were still constructed primarily through the collision of discrete images and sounds. When different media were reflexively inserted within the same space as the “characters” – as in the use of advertising in films like Made in USA (1966) or the use of video cameras in Numéro deux – the individual elements retained their relative autonomy.

It was only with the turn towards superimposition in Histoire(s) du cinéma that Godard could truly place “two realities that are more or less far apart” within the same contiguous space. Since this “space” is always shifting, with no single image allowed to attain complete self-sufficiency, the basic operating conditions of collage, which presupposes a stasis that enables the tenuous boundaries among the various elements to be apprehended, are supplanted, creating the grounds for a genuinely polyvalent montage.