Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

Montage, Movement, and the Spaces of Memory

Always sensitive to the new creative resources made available by technology, contemporary cinema's signature filmmakers are distinguished above all by an innovative approach to movement, framing, and editing that develops established paradigms in new directions.

Some, like Paul Thomas Anderson and Wong Kar-Wai, have combined fluid camera movements with rigorous editing strategies in ways that have helped to redefine the relationship between montage and mise-en-scene. The vital formal vocabularies they have developed in their finest films reflect the absorption of longstanding pictorial traditions and the dynamic reworking of earlier creative models (from film, visual art, and music).

Where ambitious filmmakers in an earlier period incorporated overt restagings of recognizable works, these films suggest instead an internalization of influence that is linked to distinctively cinematic ideas of vision and contributes, on multiple levels, to an impression of continuity within change.

Paul Thomas Anderon's The Master (2012)

The most striking aspect of the four-shot sequence from The Master above is the confluence of a musical structure; the elegant interweaving of the movement of figures, objects, and camera; and an elliptical and evocative form of montage that hovers on the borderline between contextual clarity and tantalizing enigma.

The whole sequence registers as spatiotemporally coherent because of a series of spatial matches and variations, with the right-to-left movement of camera, dolly, and figure in the second shot matched by the left-to-right movement in the third, the shift from lateral to tunnel space in the first shot echoed in the third, and the fourth shot combining and reorienting all of these micro-movements. The initially disorienting sense of space in the final shot, where we briefly lose the ability to distinguish camera and object, figure and ground, gives added resonance to the play with point-of-view in the third shot, where what seems to be a straightforward, over-the-shoulder setup becomes, in motion, something rather different. The repeatedly racked focus in that shot serves as a psychological correlate to what the protagonist seems to be experiencing, a yearning for clarity and stability that sets the terms for the shot/countershot exchanges that dominate the remainder of the film (below).

The sequence also strongly evokes the work of the most visually eloquent and iconographically consistent of American filmmakers, John Ford, with the first shot concluding with a dolly through a doorway much like the one that both opens and closes The Searchers (1956). Other filmmakers have referenced this imagery to deepen the sentiment associated with wartime loss or as an ironic comment on outsider violence, but Anderson seems to be more fully in dialogue with Ford’s visual language. Ford was the cinema’s great poet of passageways, liminal spaces, and transitions, and he gave a strong cinematic inflection to a visual tradition that, extending back through both American painters like William Sidney Mount and the 19th century prints of Currier and Ives, was rooted in the conventions of Northern European genre painting epitomized by artist such as Pieter de Hooch (below).

The paradigmatic American auteur, Ford also understood better than most the expressive power of spatial repetition and variation. In this way, the same formations in Monument Valley that evoked refuge from the “virtues of civilization” in 1939’s Stagecoach could, in Ford’s first postwar Western, My Darling Clementine, be made to participate in a very contemporary sort of mourning for those who, like the protagonist’s 18-year-old-brother James Earp, died before their time.

In My Darling Clementine, these visual tropes are brought together in a beautiful, if tentative, synthesis connecting the constitutive elements of social life (the entering Marshal with his “lady fair” and the community dance) with emblems (the paired flags and the open-air church steeple) of a nation that, in both 1882 and in 1946, was undergoing tumultuous change. Anderson encourages a complementary meditation on national construction in The Master by having his flag pass at twilight underneath San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge, a different but equally charged sort of national icon in our technologically saturated age. As with Ford, Anderson links depictions of the past, here 1946 as seen from the perspective of 2012, to anxieties about the present, as if trying to locate the roots of our contemporary malaise.

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-Wai, 2000)

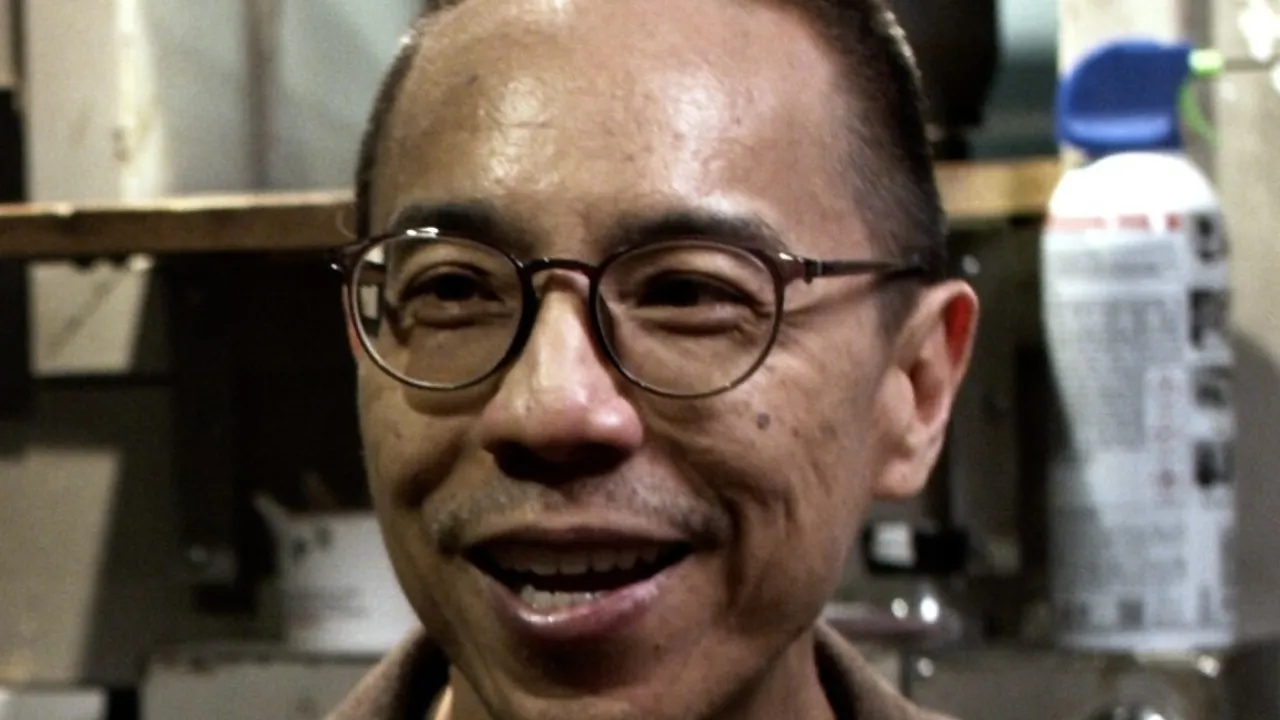

Even more acutely than Anderson and Ford, Wong Kar-Wai is preoccupied with time. His breakthrough film Chungking Express (1994, left) opens with a characteristic synthesis of formal devices that emphasize the velocity of movement and film noir-inflected retrospective narration.

Both strategies are developed much further in In the Mood for Love. As in Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo, multiple levels of performance converge as neighbors discover that their spouses are having an affair, endlessly rehearse their responses, and begin to fall in love themselves (below). Framing (such as shots of the corridor to Room 2046 where they furtively meet), camera movements, and gestures are repeated and matched throughout. The growing intimacy of the couple is conveyed through their collaborative storytelling and their joint presence in the mirror.

As always in Wong's later films, motivations are complex. Whether through ethical compunction, timidity, or misunderstanding, the central characters do not end up together.

Through a series of dramatic ellipses, 1962 becomes 1966. The concluding montage (bottom) is immediately preceded by television footage of Charles de Gaulle's arrival in Phnom Penh to deliver a September 1966 speech calling for Southeast Asian neutrality and an end to the escalating Vietnam War. The degree to which the decisions of the characters are shaped by these shifting historical circumstances remains deliberately opaque.

In the extraordinary montage at Angkor Wat, Wong instead emphasizes the gap between the tactile marks of evanescent human presence (such as the fingers pushing earth into stone) and various forms of natural decay. Significantly, several of these shots are framed as point-of-view shots from unidentified observers.

These shifts in point-of-view set the stage for the final phase of the sequence, after the protagonist departs. Forward movement towards the plant material tentatively embedded in the architecture is followed by a pair of linked shots proceeding in the opposite direction. Finally, there is a sustained lateral movement, perpendicular to the preceding three. Over the course of this unbroken shot, the music is gradually replaced by location sounds. The movement slows, but does not stop, as if the camera were an observer trying to grab hold of the fugitive moment while it inexorably slips away.