Please update your browser

Your current browser version is outdated. We recommend updating to the latest version for an improved and secure browsing experience.

The Creative Geographies of The Godfather

“Though the shooting had been done In varied locations, the spectator perceived the scene as a whole. The parts of real space picked out by the camera appeared concentrated, as it were, upon the screen. There resulted what Kuleshov termed 'creative geography.' By the process of junction of pieces of celluloid appeared a new, filmic space without existence in reality. Buildings separated by a distance of thousands of miles were concentrated to a space that could be covered by a few paces of the actors.”

Vsevolod Pudovkin, Film Technique and Film Acting (1929)

Transformations of Space and Time

Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather, Part II (1974) are among the most ambitious achievements of the American cinema, together covering a span of nearly six decades (1901-1960). The exploration of the shifting realities of American life and the mutually reinforcing metaphors of family and business are connected in the second film to a Tolstoyan reflection on history itself. As in War and Peace (1867), the travails of the Corleone family are made to intersect at critical junctures with macro-historical events: American intervention in the First World War in 1917 (linked with the San Rocco festival and the ascent of young Vito Corleone), the takeover of Fidel Castro in Cuba (1959), and the Bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 (in the concluding flashback).

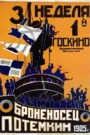

In both films, the different strands are brought together in bold montages that extend the principles of parallel editing by creating the impression that separate events in distant locations occur simultaneously and in meaningful relation to one another. In The Godfather, Coppola and his editors (Peter Zinnner, William Reynolds, Barry Malkin, and Richard Marks) explicitly acknowledge the Odessa Steps montage in Battleship Potemkin (1925) through the recurring motifs of steps, mirrors, and bloodied glass (below). However, reflecting Coppola's understanding of musical form (his father Carmine Coppola is a composer), the entire sequence is structured like and accompanied by a Bach fugue (Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, BWV 582). The pattern of development and transformation into another key takes the form of clustered shots (often in threes) suggestive of ascent and decent.

Associations of movement and action link murders in Nevada and different parts of New York and New Jersey with a baptism shot in the Basilica of St. Patrick's Old Cathedral in New York City. Through the darkly ironic juxtaposition with Michael Corleone's renewal of baptismal promises (on behalf of the nephew he is speaking for), this "creative geography" simultaneously conveys Michael's consolidation of secular power and potential damnation. In perhaps the most audacious and resonant cut (left), two different changes of state are contrasted when the imposition of salt on the child (which traditionally signifies wisdom) is paired with shaving cream (a banal liquid that contains salt). The inversion of sacramental meaning is reinforced in the following sequence when Michael Corleone makes Carlo Rizzi, father of the child who has just been baptized, perform a parody of Confession.

The Godfather, Part II

The culminating montage sequence of The Godfather, Part II (below) is both more expansive and more distended. There are significantly fewer cuts, with longer gaps between them, and the movement of the boat at the beginning of the sequence establishes the overall rhythm. Each of the three deaths (at an army base, Miami airport, and the Corleone family compound in Lake Tahoe, Nevada) is accorded greater dramatic significance than the ones in the Baptism montage of The Godfather. The stakes are raised further when the assassin Michael Corleone has sent to Florida is himself shot in a clear echo of the televised shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald's killer Jack Ruby.

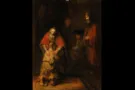

That the film does not become an associative mise-en-abîme is due largely to the force of the religious imagery that dominates the final section of the sequence. It was anticipated earlier in the film by the restaging of the Kiss of Judas and the Return of the Prodigal Son in two earlier embraces of Michael and his brother Fredo. In the final montage, the words of the guard played by Harry Dean Stanton as he opens door draws his attention to the inverted Eucharistic imagery of Frank Pentangeli's suicide. It is this image that provides the bridge to Fredo's possibly interrupted Hail Mary. The sound drops off as Coppola cuts away from the execution to Michael watching from his boathouse at precisely the moment Fredo would have completed the prayer ("now and at the hour of our death"). The strategy magnifies the sense of Michael's transgression and paradoxically makes the viewer more attentive to the truncated soundtrack.

In the process of eliminating all threats to his family's safety, Michael has tragically lost connection with almost everyone in his life and has no recourse but to retreat into memory.